Kuala Lumpur Sdn. Bhd.

Director: Andrew Ng Yew Han

Kuala Lumpur Sdn. Bhd., a documentary film by indie filmmaker, Andrew Han, premiered in October 2015 as part of the annual KL Eco Film Festival, now in its eight edition. As the title suggests (‘sendirian berhad’, Malay: ‘private limited’), the film tackles an increasingly critical issue in the lives of urban citizens in Kuala Lumpur, namely the encroachment of privatization on public spaces and the hegemonic representation and commodification of KL as a ‘global city’ fit for financial and real estate investment in the 21st century.

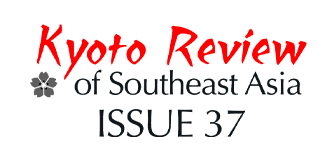

Kuala Lumpur Sdn. Bhd. can be seen as a continuation of the themes explored in the 2012 award winning documentary M-C-M’: Utopia Milik Siapa?, a film on capitalist development and home ownership in KL, where the director was a member of the production team. 1 While the earlier film centred on the increasing unaffordability of homes and the correspondent rise of household indebtedness among Malaysians (as of 2015, it stands at 87.9% of national GDP, second only to South Korea in Asia), especially its impact on the young working population, Kuala Lumpur Sdn. Bhd. seeks to tell the story of a small group of urban activists fighting to save a small public park in the heart of historical Kuala Lumpur (the Merdeka Park) from being demolished to make way for a 118-storey megatower, projected to be the tallest building in Malaysia, eclipsing the famed Petronas Twin Towers.

In keeping with what the director said was the ‘minimalist’ tone and ‘guerilla-filmmaking’ techniques of his earlier work, we see glitzy, corporate promos by the KL financial elite, such as tycoon Francis Yeoh (of the large YTL conglomerate) waxing lyrical about KL’s premier status as an investment and business-friendly haven, thrown into sharp relief when juxtaposed in a montage of images which included the story of Arumugam, a middle-aged KL resident and cab-driver, who spent 23 years of his life in decrepit temporary housing, still waiting for a permanent home promised by the KL City Hall when they were evicted from their original dwellings in Sentul (now a thriving residential and commercial development under YTL). From these two perspectives, the documentary raises two fundamental questions surrounding Kuala Lumpur’s strategic location and role within Malaysia’s political economic system. Both questions are intrinsically tied to the way the state and capital nexus has taken shape in the course of Malaysia’s history of capitalist development.

[youtube id=”VPmOWfZwy0Q” mode=”normal” maxwidth=”900″]Kuala Lumpur Sdn. Bhd. Official Trailer #1 (2015) – Documentary HDThe first issue, depicted rather prominently in the film, is the imposing role played by the Dewan Bandaraya Kuala Lumpur (DBKL, or KL City Hall) in all matters related to urban development and land use, project approvals included. The director leads us, from the opening credits, with a news report and voiceover by Prime Minister Najib Razak on the impending plans for the 118-storey megatower, the state’s shadow looms large over how the story would develop over the next 45 minutes of this documentary. We learn over the course of the small band of activists’s struggle to reclaim ‘Merdeka Park’ (also, known colloquially as the ‘Tunku Park’, named after Tunku Abdul Rahman, the country’s first prime minister, who declared Malaysia’s independence in a stadium, not far away) the mammoth task and obstacle besetting ordinary urban citizens such as themselves in having their voices heard and considered by the local government on this issue. This land has been acquired by Permodalan Nasional Berhad (PNB), a financial giant, responsible for issuing and managing unit trust schemes on behalf of the Bumiputera community (the Amanah Saham Bumiputera scheme, since the 1978), to build what is to be named the ‘Menara Warisan’, a 118-storey building, to house PNB’s offices, develop a luxury hotel as well as other commercial units, at the heart of KL.

In interviews with an expert on local government issues, it is clear that DBKL operates behind a veil of bureaucratic opacity, where KL residents are systematically kept in ignorance of their rights and the rules governing the DBKL in the approval of development projects, with minimal consultation and input from the residents themselves. This turns out to be only the tip of the iceberg as far as the democratic deficit is concerned, where KL residents have no right to vote for their local government nor the city mayor, in spite of a total budget of RM2 billion according to figures in 2013. 2 It is what economist Edmund Terence Gomez has described as the two dominant features of contemporary Malaysian political economy, namely the developmental state and neoliberal capitalism, which perfectly sums up the personal tragedy faced by Arumugam and his cohort from Jinjang Utara; systematically coerced and relocated by DBKL, at the behest of private developers, and later left to live indefinitely in substandard temporary dwellings for over 20 years, whilst other luxurious and high-end residential developments mushroom around them.

The spatial impact of the latest phase of neoliberal urban development in KL cannot be understated, represented in ironic fashion in the film, where at one point, Arumugam while giving a walking tour of his decrepit surroundings, leads us to a beautiful, scenic park, literally across some simple fencing from his temporary neighbourhood (read 20 years), which he claims are prime land for high-end condominiums and for those who can afford them (a reason why they will not be permanently resettled here). In time, they will be uprooted again to make way for the ‘target market’ of the slick, corporate informercials by InvestKL, the ‘global citizens’ in a globalized world fit for a ‘global city’ such as KL.

The second fundamental question explored in the film is the overwhelming, preponderant presence of what is now a permanent feature of Malaysian capitalism, the fact that the 118-storey ‘Menara Warisan’ is a development project driven by Permodalan Nasional Berhad (PNB), a government-linked investment corporation (GLICs). 3 Watching the group of urban activists, many of them young, artistic, and cosmopolitan in outlook, face up against the gargantuan financial conglomerate with state backing, one cannot help but feel that their cause, to defend that patch of green space, Merdeka Park, had the perfect makings of a home-spun, Greek tragedy.

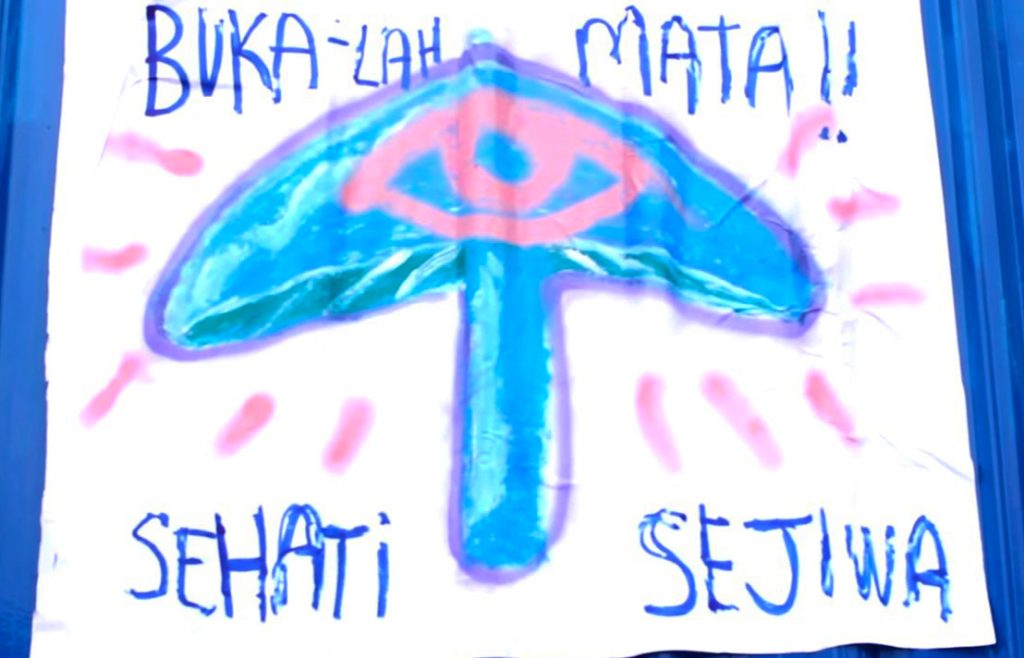

How can men, in spite of their heroism, ultimately outwit and overcome forces beyond their control, which in contemporary terms are no longer ‘gods’ but seemingly all-powerful nonetheless, concretely represented by DBKL’s unreserved approval of PNB’s plans? 4 Also, a major social contradiction exposed in the course of the documentary is the perennial question of ethnicity in Malaysian politics. Why did the struggle for Merdeka Park fail to rally thousands other KL residents to their cause, in spite of what has been a time of effervescent, social mobilization since 2007, the time of Bersih and countless other social protests that took place in KL? Even as Andrew Han expressed back in 2013, the struggle for Merdeka Park potentially have the makings of a similar uprising as seen in the Gezi Park protests in Turkey. Why the abject failure in the Malaysian case?

There may be many reasons for this, especially on hindsight, but could it be that one major factor at play in the present case is the fact that PNB’s development project is tied to its explicit role in carrying out the Bumiputera agenda of acquiring equity on behalf of narrow communal interests? What are the chances of protesting a project driven by a GLIC that is fundamentally implicated in the hegemonic ideas of Malay and Bumiputera development, one that has enjoyed legitimacy as a ‘national agenda’ since the inception of the New Economic Policy in the 70s?

Ultimately, the documentary raises more questions than answers, which is in keeping with what the director has conceived, that Kuala Lumpur Sdn. Bhd. would be an educational aid in an on-line open learning program. 5 It comes at a significant moment in Malaysia’s developmental path, especially in a time where the 1MDB scandal, a GLIC nonetheless, has raised the Malaysian public’s consciousness of corruption linked to the Najib Razak administration.

What films like Kuala Lumpur Sdn. Bhd. and the earlier, M-C-M’: Utopia Milik Siapa?, could do is to deepen analysis and questioning of an urban developmental model that is tied to Malaysia’s political economic framework of the developmental state and the post-Mahathirist neoliberal capitalist strain. The question is not corruption and despotism in the one case of 1MDB, but rather the very system itself that makes developmental decisions the monopoly of a specific nexus between unelected state bodies like the DBKL and the equally unelected directorate of the GLICs, such as PNB, whilst ordinary KL citizens have minimal participation in how their spaces are governed.

Thus far, no social protest movement has been able to mobilize or capture the imagination of the discontented masses in Malaysia save the Bersih movement, centering mainly on electoral reform and combating corruption. Discourses on wealth and income inequalities has failed to generate the kinds of popular outrage seen in the global Occupy movement and the Spanish indignados of 2011, now taking on institutional political expressions seen in the growing support for Podemos in Spain, the election of new British Labour Party leader, Jeremy Corbyn, and the enthusiastic campaign of U.S. presidential hopeful, Bernie Sanders. This failure, by no means unique to the Malaysian case, invites deeper research and understanding of power and inequality in the Southeast Asian region, summed up most pertinently by Pasuk Pongpaichit and Chris Baker in their recent edited volume, Inequality in Thailand: “In sum, neoliberalism and trends within capitalism may contribute to rising inequality in Asia, but there are other factors that may be more important, including development policy, old forms of hierarchy, and the persistence of oligarchy and strong conservatism against democratic principles.” 6

These ‘other factors’ may suggest more fruitful engagements with the question on how the Malaysian variant of economic development has been successful in keeping the lid on growing aspirations for local participatory democracy, especially in a time of increasing state austerity, corporatization of public spaces and youth indebtedness.

Reviewed by Boon Kia Meng

(ASAFAS, Kyoto University)

Issue 19, Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia, March 2016

Notes:

- “M-C-M’: Utopia Milik Siapa?” is available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hv9bWjgEXtc ↩

- Tricia Yeoh, “Who governs City Hall?” in The Sun Daily, 6 November 2013. ↩

- ‘GLCs reportedly comprise 36 per cent of the Malaysian stock exchange’s capitalisation and 54 per cent of the entities that make up the Kuala Lumpur Composite Index. The Malaysian government controls GLCs through its government-linked investment companies (GLICs) — gargantuan and powerful investment arms including Khazanah Nasional, Permodalan Nasional Berhad — and the Ministry of Finance.’ See: Hwok-Aun Lee, “Political preference crowding out private enterprise” in http://www.eastasiaforum.org/2015/01/14/political-preference-crowding-out-enterprise/ (accessed on 7 February 2016) ↩

- Interestingly, as will be discussed in the review, the struggle against PNB bears resemblance in microcosmic form what Karatani Kojin has named the trinitarian nexus of Capital, Nation and State (read GLIC, Bumiputera agenda, and DBKL in the present case). ↩

- Available online, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wrx5Jbl3IzM ↩

- Pasuk Phongpaichit and Chris Baker, Unequal Thailand: Aspects of Income, Wealth & Power, Singapore: NUS Press 2015. ↩