Although there is no specific national data regarding number of suicides, there is a possibility that this number will continue to increase until the end of the year. This increasing number of suicide is a concern for all. What is actually happening at the moment within the world of Indonesian children/teenagers? Why are the suicide cases among Indonesian children/teenagers increasing? What are the motives behind these suicides? A deeper exploration is needed in order to answer these questions. This short article, however, wishes to highlight the phenomenon of child/teen suicide in the context of local Indonesian culture, with special reference to Gunung Kidul regency (in Yogyakarta province).

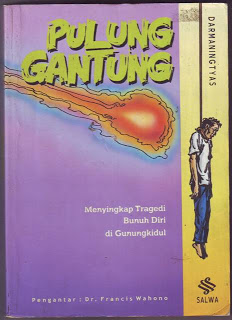

Pulung Gantung

The Gunung Kidul regency (Yogyakarta) is known as an area with the highest child/teenager suicide rate in Indonesia. For the last five years, the suicide rate in the area has been relatively high. According to the local police, throughout 2011 there were 28 cases of child/teenager suicide. A note in Wahana Komunikasi Lintas Spesialis (Communication mode for specialists) magazine mentions that the suicide rate in Gunung Kidul regency was nine in every 100,000. For a comparison, the suicide rate in Jakarta (Indonesia’s capital city) was only 1.2 cases in every 100,000.

In this respect, there is a local term regarding suicide: “pulung gantung.” It refers to a local belief concerning the reason why someone decides to commit suicide; that s/he received a “pulung” (prophecy) in the form of star at night. The star is a rounded reddish or yellowish light with a blue flash tail – akin to a space comet. It would fall very quickly with a direction heading toward the house (or near the house) of the suicide victim. The victim would then commit suicide by means of hanging themselves – this is why it is called “gantung” (to hang).

In this respect, there is a local term regarding suicide: “pulung gantung.” It refers to a local belief concerning the reason why someone decides to commit suicide; that s/he received a “pulung” (prophecy) in the form of star at night. The star is a rounded reddish or yellowish light with a blue flash tail – akin to a space comet. It would fall very quickly with a direction heading toward the house (or near the house) of the suicide victim. The victim would then commit suicide by means of hanging themselves – this is why it is called “gantung” (to hang).

“Pulung gantung” always spreads by word of mouth within the community after a suicide has taken place. It seems like a justification over one’s fate that needs no further explanation. 1 Nonetheless, local people do not put aside the apparent fact that one has gone through personal problems that are beyond their capacity to handle before committing suicide that becomes “common knowledge” in the community. For example, an incurable disease, unpayable debt, no hope of continuing education, or heartbreak caused by a lover or husband/wife.

One case may illustrate this issue. On 24 December 2011, a 15 year old junior high school student, Cicilia Putri, was found hanging. She had hung herself with a scarf to the wooden bean in her room. As the news spread, local people believed that a few days before the incidents a light with a tail was seen falling near her house. Nonetheless, both of her parents who live in Bandung (West Java) suspected that she decided to end her life due to high stress after being left by her boyfriend.

This shows how “pulung gantung” is taken as a part of a “culturization process” in society and suicide cases are treated as a natural cause. As such, it has become common knowledge among the local people that it stands as a “lesson” in how to solve a life problem that is beyond logic and common sense.

Life crisis and the politics

It’s been widely reported that suicide is not motivated by one single factor as commonly accepted, due to economic pressure. Those who commit suicide are not always from the poor income families with low level of education or living in rural areas.

Suicide also takes place in urban settings and to those who are considered financially better off and with a good educational background. Neither the economic background nor education levels guarantee someone will be free from stress and capable of handling life’s problems rationally.

Although economic factors could be singled out as a prime motive for suicide, as mentioned above, child/teenager suicide forces us to look beyond these factors. Children are forced to face a complex reality beyond their emotion control and capacity to overcome certain life problems and when cornered, they decide to choose “short cuts” to find solutions. Since 1998, this nuance became more pronounced within the context of socio-political changes in Indonesia. With the decentralization of politics, local governments are preoccupied with political contestation, instead of paying any attention to the welfare of children/teenagers in their respective areas as socially expected. Yet, families that are supposed to provide support for child development face a number of social challenges. Either the father or mother (or, both) no longer have time to attend to the needs of their children as they used to, children become caught between personal problems and the complexity of social challenges in their lives characterized by violence and the atomization of inter-personal relations. The challenge for Indonesia in the 21st century is to provide the right spaces and conditions for the balanced development of the emotions and logic of its children/teenagers.

Abdur Rozaki

Lecturer at UIN Sunan Kalijaga Yogyakarta

Researcher at IRE (Institute for Research and Empowerment)

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Issue 12 (September 2012). The Living and the Dead

Notes:

- See Darmaningtyas, Pulung Gantung: menyingkap tragedi bunuh diri di Gunung Kidul (Yogyakarta: Penerbit Salwa: 2002). ↩