Introduction

The purpose of this paper is to define the processes and techniques used in trial of the visualization of ethnic identity by examining the case of Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park (Taman Budaya Tionghoa Indonesia). Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park is an ongoing museum building project by one of the Chinese Indonesians social organization, Paguyuban Sosial Marga Tionghoa Indonesia (PSMTI ) and it is aimed to exhibit the culture and history of Chinese Indonesians in Taman Mini Beautiful Indonesia in the outskirt of Jakarta.For the valid examination of the Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park, I will be using Clifford’s concept of “the museum as a ‘contact zones.” In “Routes: Travels and Transitions in the Late 20th Century,” Clifford examines four museums which have exhibitions of North American Indians in the northwestern coast. Clifford points out that the museums were originally a site of mass-control, wherein the dominant group collects, organizes, and displays the culture of the minority. However in present days, they became the venues for the minority groups’ identity formation and function as “contact zones” for both groups. 1

In this paper, I will first discuss the museum plan of Chinese Indonesians, one of the ethnic minorities in Indonesia, with the detail of museum’s construction plans, it’s planner, location, current state and problems. Then, I will illustrate the process of how ethnicity is symbolized in the museum and the museum thus became the “contact zones” of the nation and the various ethnic groups.

In multi-ethnic nation, Indonesia, the visualization of the ethnicity takes various forms from the ornaments in the shopping malls and the statues in streets, to distributed election campaign paraphernalia. These visualizations contain possible messages for specific purposes such as business or politics. In case of Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park, the message is conveyed from the Chinese Indonesians to the nation.

In this paper, terms such as Tionghoa, the Hokken pronunciation of “Zhonghua” is translated as “Chinese Indonesian.” 2 In addition, terms refereeing to the ethnicity such as Indonesian “suku”, “suku bangsa”, and “esnis” are translated as “ethnicity”. 3

Background

May 1998 was memorized as the moment of both liberation and the fear by the Chinese Indonesians. The 32-year long Suharto regime fell down as the result of the nation-wide riots which eventually Chinese Indonesians were liberated from the various legal restrictions casted by Suharto. At the same time, by becoming the target of violence in the riots, it revoked the fear among the Chinese Indonesians simply for being existed as Chinese Indonesians.

On 12 May 1998, during a protest meeting at Trisakti University in western Jakarta which was criticizing the Suharto administration for the economic crisis since 1997, someone fired gunshots, resulting in the death of 4 students. This incident triggered large-scale, nationwide riots. Starting from Jakarta, it spread to different areas, including Medan, Solo, and Palembang, resulting in the deaths of more than 1100 people. 4 What started as a protest against the Suharto administration turned into an anti-Chinese Indonesian movement because of the stereotypical speculations that the Chinese Indonesians were associated with the economic benefits under the Suharto administration. In the center of the commercial area known as Glodok in Jakarta, there were numerous incidences of arson and assault against Chinese Indonesian women.

Suharto eventually resigned on May 21, 1998. And ever since, Indonesia has experienced a dizzying change in political power, starting from Habibie, to Abdul Rahman Wahid, Megawati up to the present Yodoyono administration. With the change in political power, the revision of legal restrictions concerning Chinese Indonesians also proceeded at a rapid phase. The history of the changes in laws concerning Chinese Indonesians are described in detail in the works of Suryadinata (2003) and Lindsey (2005). In these works, they point out the elimination of restrictions regarding culture, religion and language, which occurred between October 1999 until July 2001, during the administration of former president Abdul Rahman Wahid. 5 Moreover, the “12th Law of 2006: New Nationality Act,” approved on 1 August 2006, is hailed as an landmark revision in Indonesian jurisprudence concerning the Chinese Indonesians. 6

The law revisions to assure the equality of Chinese Indonesians in their socio-cultural and political life has been promoted continuously and environment where Chinese Indonesians can freely express their ethnic identity has being set in place in Indonesia. Initially, the legal revision and the rise of the liberalization of expression should contribute to the freedom of expression to express ethnic identity of each individual and it is not always the case that right is exercised to express an ethnic identity for a group However, Chinese Indonesians had a demand to be promote recognition as one of the Indonesian ethnic groups.

The anti-Chinese Indonesian movement in May 1998 was caused because of negative stereotype against Chinese Indonesians among non-Chinese Indonesians . To their eyes, if it allows me to oversimplify, “Chinese Indonesians” was seen as an exclusive group that controls the state of the economy and which bears no relation to “native Indonesians.” In this stereotypical image, there was no space for the individual Chinese Indonesian identity.

The riots in May 1998 made clear that the Chinese Indonesians were recognized as one monotonous group by the others, it seems natural for Chinese Indonesians to come up with the idea of forming a positive image of Chinese Indonesians as one ethnic group to counter the above mentioned stereotype in order to avoid the repeat of tragedy of May 1998. Then, there is the problem of justifying and defending the existence of “Chinese Indonesian” as an ethnic group, for it threads on the same problems as other “native Indonesian” groups like the Javanese and the Sundanese. Realizing this situation, the formalization of religion, language and cultural events have been worked on and Chinese Indonesian ethnicity is in the process of being visualized.

Planner: Chinese Indonesian Group and the PSMT

It is not clear when the idea of the Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park was conceived and by whom. However, at this point, it is the project of the PSMTI, whose headquarters is in Jakarta. There are many Chinese Indonesian organizations in Indonesia. In Jakarta alone, there are over a hundred groups. Among these groups, what features does the PSMTI possess and what part does it play among these organizations?

Chinese Indonesian organizations or associations can roughly be categorized namely, 1) organization by the place of origins such as Fujian and Yongchung, 2) organizations by the same sir names such as Rins or the Yus, 3) organizations by religious affiliation like Confucianism or Buddhism, 4) alumni associations of the Chinese Language School, before they were closed in 1966 7 and 5) social organizations Bringing together these various organizations from all over Indonesia into representative umbrella groups are the Jakarta-based PSMTI and the Perhimpunan Indonesia Tionghoa (INTI). 8

The PSMTI and the INTI were originally one organization, established after the May 1998, when it was found out that there was no nationwide social organization that came to protect Chinese Indonesians. In 28 September 1998, it was established with as an organization to facilitate the mutual aid among Chinese Indonesians. The founding representative of the organization was former military personnel, Tedy Yusuf. In 1999, Eddy Lembong, the president of the pharmaceutical company Pharos, represented the organization and INTI was established as a separate entity from PSMTI. According to talks from PSMTI and INTI members, the biggest reason for the break-up of the two organizations was inexperience of the Chinese Inondesians in the field of leadership and they seemed to not be used to consolidating opinions. This is probably due to the fact that Chinese Indonesians were not allowed to organize themselves during the Suharto administration.

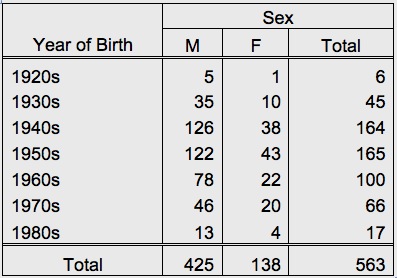

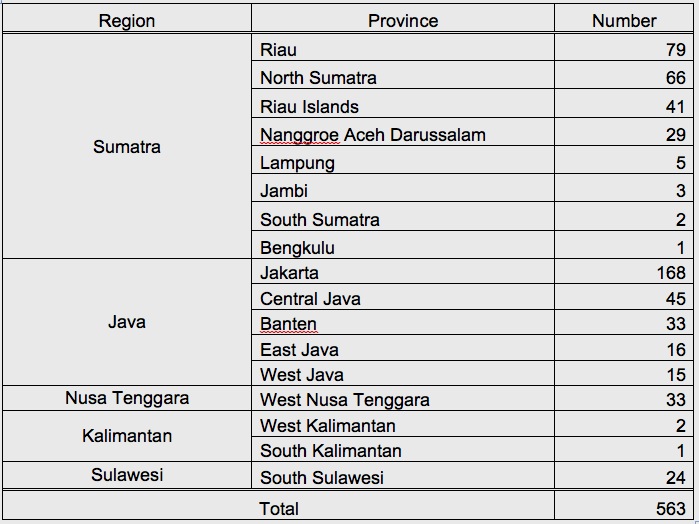

Then, what kind of members comprises the PSMTI? As of present, PSMTI has about 560 members. Although the supporters of the PSMTI activities are probably much larger in number than the registered member, I would like to try to draw the characteristics of PSMTI by looking at the features of full-pledged members for now. First, in terms of age group and sex, Table 1 clearly illustrates that most members are males born in 1940s and 1950s. From these members, the possibility is high that they received education from the Chinese Language Schools before they were closed. Next, in terms of place of residence, Table 2 illustrates that more than 40 percent of members are reside in Jakarta and other provinces in Java. And in terms of occupation, more than 90 percent of members are designated in business. 9

From the data above, even though PSMTI keeps expanding as an umbrella organization for different Chinese Indonesian groups throughout the nation, the members who has more direct influence to the Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park are more likely the male supporters received their education from the Chinese Language School and reside in the island of Java. Given the description of PSMTI given above, let us move on to the place selected by them as a venue for the construction of the museum, namely Taman Mini.

[quote]Table 1: PSMTI membership distribution by age and sex as of Sept. 2006[/quote]

Location: What kind of Place is Taman Mini?

Taman Mini was an important part in Suharto’s cultural policy. Pemberton (1994) and Kato (1993) elaborated the roles that Taman Mini in Suharto’s cultural policy as below. According to Pemberton, to deny the memory of the massacres and political purges that characterized the beginning with September 30, 10 starting in early 1970s, the Suharto presidential couple started to pour effort into politicalization of “culture” and the creation of the “tradition” as epresented in Taman Mini. Pemberton, discusses the 1983 “traditional” Javanese wedding of Suharto’s second daughter Siti Hediati held inside the Hall at Taman Mini and the reconstruction of the Surakarta royal palace in the same chapter and explains that they are the two examples that Suharto tried to search the basis for the creation of “tradition” in colonial period because of its time distance form the 1960s.

Kato describes the importance of Taman Mini and the Education and Culture Ministry’s “catalogue production and documentation” project of the 27 Indonesian states as the method of packaging local culture and ethnicity under the control of the central government. Kato also points out that both projects subsume the diversified of multi-ethnic Indonesia not by the unit of ethnic groups but by administrative unit as a process of national integration. As a result, Chinese Indonesians, who are not concentrated in any one particular administrative unit, were left out and become an “invisible” ethnicity.

From the discussion of both authors, there is an attempt by the Suharto administration to negate unpleasant memories of the recent past and Taman Mini was a system set up by the central government to package the “tradition” of the different ethnic groups found in the country to serve as the nation’s new collective memory. Let us look into the details of Taman Mini below.

The idea for Taman Mini was announced on August 1971, as a project of the “Our Hope (Harapan Kita) Foundation, which was headed by Tien Soeharto, the president’s wife. The particulars of the idea cannot be fully ascertained. But according to Tien Soeharto herself, Disneyland served as a model for Taman Mini. However, it is also possible that the idea came from the similar miniature parks that were opened around the same time in Thailand and the Philippines. 11

Apart from the particulars of the of the plan, 100 hectares were secured about 5 kilometers away from the international airport, Halim Airport, in Pondok Gede. In the process of obtaining the site, protest actions by students and residents arose but were eventually suppressed by the Suharto administration (Anderson 1973). Suharto’s strong attitude in this process suggests that Taman Mini was not planned as a recreational institute like Disneyland.

The aims and objectives of Taman Mini published in 1975, clearly phrase our the role of Taman Mini in Suharto’s cultural policy such as Taman Mini is a institution to visualize and express the Indonesian nation and its people in the miniature. In detail, there are six targets as follows: 1) building and strengthening love for the motherland, 2) enriching and renewing the sense of national union and unity, 3) appreciating and enhancing the Indonesian culture that has been inherited from the ancestors, 4) introducing the culture, natural wealth and others to the people of Indonesia, 5) utilizing the tourism industry ,and 6) helping actively the government’s 5 year plan (Taman Mini “Indonesia Indah” 1978:46-47).

The Taman Mini facilities was organized in the following manner. At the center of the park is a man-made lake on which the entire Indonesian archipelago floats, from Papua to Sumatra. Surrounding the lake are the 27 states of the Indonesian archipelago and their respective pavilions.14 On the outer areas, different museums, mosques, churches, an orchidarium and an aviary were layout. The pavilions are in the style of the representative “traditional” ethnic house of the state it represents. Inside the pavilion are displays of wedding clothes, musical instruments and crafts. On weekends, “ethnic” arts such as dance and music are occasionally performed inside these pavilions.

Taman Mini originally opened with 27 provincial pavilions 12, the different religious institutions, the Indonesian archipelago in miniature, the Pancasila monument and the orchidarium in 1975. The fact no major museums were built until the 1980’s may define that the pavilions of the different states as the nucleus of Taman Mini and given its central location around the artificial lake. (Taman Mini “Indonesia Indah” 2006b)

In the 1980’s, different museums were built. However, aside from the Indonesia Museum and the Stamp Museum, most museums built were science, resources and energy-related museums. This was the result of the emphasis given on development by the Suharto administration. Museums that represent ethnicity like the Chinese Indonesian Cultural Museum still cannot be seen in the Suharto administration’s Taman Mini.

Aside from packaging ethnicity and the unitization of administrative areas, Taman Mini during the Suharto administration became a place where the creation and presentation of “tradition” and Suharto’s power and Taman Mini bilaterally influenced each other. Due to the different official functions that were held in Taman Mini, of which Suharto’s second daughter’s wedding was representative, Taman Mini was given national authority. At the same time, the same functions in Taman Mini solidified Suharto’s place in “public” Indonesian culture by backing up his ideas of traditional culture.

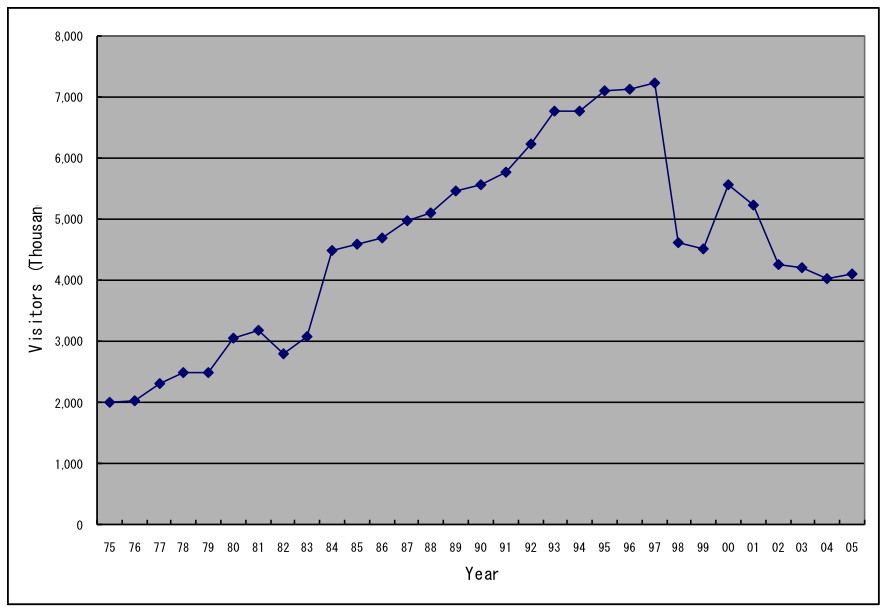

Suharto’s power of the sphere of culture as symbolized in Taman Mini and the concepts of packaged ethnicity and culture were disseminated through schools and television broadcasts and shared by large audience. Needless to say, these ideas and concepts are also shared by the significant number of the visitors. Graph 1 shows visitors numbers of Taman Mini throughout the 30 years since its inauguration. From the inauguration, Taman Mini received approximately 14 million visitors. During the 1980’s, visitor numbers saw a dramatic increase. In 1997 alone, before Suharto’s fall from power, more than 7,200,000 people have visited there. Even after 1998, more than 4,000,000 visitors were recorded to visit every year. This implies that Taman Mini’s influence shows no sign of weakening.

[quote]Graph 1: Number of visitors to Taman Mini, 1975-2005[/quote]

If we take into consideration the significance of Taman Mini in the national cultural policy and its impact to the Indonesian public, it is clear that the selection of Taman Mini as a venue for the Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park is for Chinese Indonesians to be recognized as one ethnicity by the state and accepted by the Indonesian people. As Clifford points out, “the tribal or minority museum and artist, while locally based, may also aspire to wide recognition, to a certain national or global participation.” (Clifford 1997:122) PSMTI believes that creating a museum within Taman Mini ensures a place for Chinese Indonesian ethnicity in the Indonesian nation. 13

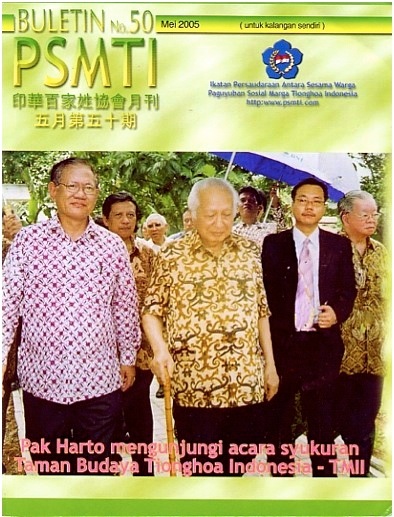

However, this concept of the state is represented by Suharto regime’s and not the present administration. As far as the PSMTI is concerned, the Suharto administration represents the state. This can be seen in the front cover of used for the organization’s bulletin. Here, the photo of Suharto, who joined a Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park-related function with Tedy Yusuf.

The planned Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park became a possibility because of the lifting of the remarkable restrictions against the cultural activities of Chinese Indonesians with the collapse of the Suharto administration. The plan also indicates that the systematic control of ethnicities based on the administrative unit began to lose its power. On the other hand, Suharto’s method of packaging ethnicities by the wedding clothes, dances, and the authority of Taman Mini remain accepted by the supporters Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park without any other alternatives. The Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park can be seen as a belated assimilation into the Suharto regime’s ethnicity policy.

The Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park plan details

The first related article on the Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park in PSMTI’s publication was in PSMTI’s newsletter, on issue number July 4,2001. In this article, it was proposed that Candra Naya, the historical building of Chinese Indonesians located in the west of Jakarta, be dismantled and rebuilt inside Taman Mini. At this point, the museum was simply referred as the “Tionghoa Museum.”

Details about Candra Naya will be related later. The article suggests two facts such as that PSMTI was the main organizational body in planning the museum as of 2001, and the historical importance of Candra Naya. In July 2003, an appeal was presented tot he special state governor Sutiyoso for the dismantling and reconstruction of Candra Naya inside Taman Mini by the owner of Grup Modern, a Chinese Indonesian enterprise. However, this was rejected. As a result, a replica of Candra Naya will be built inside Taman Mini. 14

PSMTI presented an original plan for the Chinese Indonesian Museum to the “Our Hope” Foundation in November 2002. At first, the plan was named as “Museum Budaya Tionghoa Indonesia.” Though the name has been changed later, the Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park plans have been referred to as “museum” till the present day. On January 6, 2003, Suharto, the current president of the foundation permitted PSMTI to use two hectares inside Taman Mini for the museum.

The plan was first mentioned in Taman Mini’s annual report in the 29th issue for the year 2004. In two facing pages, the museum is introduced with the words of Ali Sadikin, the governor of Jakarta during the inauguration of Taman Mini and a former military personnel during the Sukarno administration: “I fully agree with the plan to build a Chinese Indonesian Cultural Museum, as the Chinese Indonesian is part of the Indonesian nation.” 15 Then, the initial plans for the Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park is followed by a picture of a lion dance inside Taman Mini. The format used for the pavilions of the administrative units is applied here such as the combination of photos of architecture and ethnic dances.

According to the Public Relation Office of Taman Mini, the Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park was originally planned by Taman Mini. Taman Mini has plans to build separate museums for the different major immigrants to Indonesia, including Arabs, Indians, and Chinese and these museums are sponsored by ethnic organizations like PSMTI. 16 Up to now, there is no concrete proposals for the museums of Arbs and Indians. Only for the Chinese-descent, the both PSMTI and Taman Mini share the common interest and the plan is proceeding favorably. Although the true facts regarding to the plans of ethnic museums by Taman Mini are not clear, the Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park can be seen as a significant change in Taman Mini in terms of the interpretation of the ethnicity by the government.

In blueprints for the planned Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park were drown by Parahyangan University in Bandong. 17 In the original plan with this blueprint, assemblage of the collection started in April 2003, then soft opening was planned in April 2004, and the completion was expected in January 2005. However, because of the changes of design and the difficulty in fund razing, the plan has only proceeded to the set up the gate guardian lions imported from China in as of August 2006. Regarding to the change of the design, the full-scale modification designs by the Chinese private company Xiamen City Planning Group replaced the original plans in December 2005. For the fund-raising, according to the Chinese-language television news “Metro News,” only 18% of the needed funds have been collected

A number of reasons can be thought of for the difficulty in obtaining funds. The most significant reason would be that publicity was limited to Chinese-language media, the PSMTI Bulletin and Jakarta-based papers till middle of 2006 and large scale fund-raising project appealed to the general public. 18 Another reason was that there were opinions the final adopted designs were too “Chinese” and that it hardly symbolized the Chinese Indonesian culture. 19 Among those who supports the idea of establishing the museum of Chinese Indonesians , there are those who does not agree with the current design of the Chinese Indonesian Culture Park.

Although there are opposing opinions against the current design of Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park, more important factor is that there are no other alternatives suggested. This shows that no discourse has been established to express Chinese Indonesian. Granted that there is a feeling of uneasiness in the PSMTI’s blueprints for the park, there is no agreement on how to express the “Chineseness” or the “Chinese Indonesian ” which are not “Chinese” for the museum. The techniques for expression of “Chinese Indonesianness” are still in the experimental stage.

The Over-all Image of the Museum Plans

Now, what are the contents of PSMTI’s outline of the museum that is to symbolize Chinese Indonesians ? In the following, I will examine the museum’s ideology as published by PSMTI and the current designof the buildings.

PSMTI’s proposal consists of the following:1) a letter calling for contributions, 2) the proposal sent to the “Our Hope” foundation, 3) a summary of the purpose of Taman Mini according to Tien Soeharto, 4) the background of the project, 5) the purpose of the project, 6) the keystoneof the project, 7) a map of Taman Mini, 8) the construction schedule, 9) a cost estimate of the project, 10) the museum’s organizational chart, 11) the museum comittee’s name, 12) a conclusion and 13) a donation form. Of these items, numbers 4,5 and 6 show the ideology of the museum.

In the background, Indonesia is originally composed of ethnicities from different parts of the world and each ethnicity has different religions and cultural backgrounds. In the case of Chinese Indonesians , they are one of the ethnic groups in Indonesia who migrated there 500 years ago. What is emphasized here is the diversity of multi-ethnic Indonesia and Chinese Indonesians as one of the ethnicities in Indonesia.

In the purpose, it says that the museum will be build in order to exhibit where from and how Chinese Indonesians originally migrated, how they lived, and how they interacted with their surroundings. A sentence without a subject then follows and stays that experience of fighting in the during the independence war, hardships went through in the old days, ideals, and thoughts will be also exhibited. In the end, the museum is stipulated to not be a Chinese museum or a religious institution. The intent of the museum is said to unite the different ethnic groups including the Chinese Indonesians in order to establish the social justice and the prosperity.

From the aims and outline above it is clear that there is an attempt to avoid expressions which provoke the image of “China”, as a result of the memories of the discrimination experienced under the Suharto administration and the violence of 1998. However, if we look at the construction plans, Chinese expressions have been adopted in a very clear manner. The over-all image of the new Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park can be seen in picture 2. The main structures include 1) a 7-storey octagonal pagoda, 2) a replica of Candra Naya, 3) a replica of the Forbidden City, 4) a gate made from materials imported from China, 5) a Chinese junk and 6) an imitation of Chinatown markets found throughout the Indonesia. In the original plans drawn by the Parayangan University, there was an residential architecture instead of the replica of the Forbidden City and the designs gate and pagoda were vastly different. Also, the position of the different buildings have been changed.

Aside from the Candra Naya and the Chinatown replicas there are buildings that symbolize so-called “China”. The gate and the replica of the Forbidden City can be seen to evoke Beijing, the political center of China. The connection with Beigin is very obvious in case of Forbidden City, but it is also evident for the gates in pictures 3 and 4. The pictures explain that the gate was modeled after the gates of Western Qing Tomb and Eastern Qing Tomb which represent the Qing dynasty. According to PSMTI, they commissioned a gate that reflects the 5 pillars of the Indonesian national policy of Pancasila. 20 However, it is rather difficult to associate the present design gate as the representation of Pancasila.

Though the origin of the majority of Chinese Indonesians can be traced to the southern part of China such as Fujian and Canton, and this design of Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park was drew by the office in Fujian, the museum do not have any representation of southern of China. Instead, there is an extremely simplified composition of Chinese Indonesian equals China equals Beijing. Moreover, the replica of the Forbidden City, that is supposed to be used as the exhibition hall, the heart of the museum.

There are three possible reasons for placing the replica of the Forbidden City as the heart of the museum. The first is a political interpretation. It is an attempt to situate the political power of Baijin within the context of Chinese Indonesian history Second is a matter of publicity. It was chosen as a representation of Chineseness Since the Forbidden City was well-known among Indonesians in general. 21 The third reason is relating to the tradition of representation of ethnicity in China itself. In China, ethnic representation in Fujian or Cantonese is not necessarily perceived as Chinese ethnicity. In other words, when one tries to express Chinese identity in China, one has to adopt the Chineseness which is represented by Hans and same logic applies to the Chinese Indonesians . When Chinese Indonesian wants to express themselves as one ethnic group, they must adopt the Chineseness represented by Hans.

At any rate, a building which visualize the history and culture of 500 years Chinese Indonesians is not placed as the center of the museum. The only building that tell the story of the history of Chinese Indonesians is Candra Naya, which will be discussed in the next section.

Candra Naya

Candra Naya, located in West Jakarta’s Gaja Mada street, is one of few buildings that show Chinese-style architecture during the Dutch colonial period. Constructed in the latter 19th century, it was one of three residences built by sons of Khouw Tian Sek, a Chinese officer. It later became the residence of Khouw Kim Au, the last executive officer of the Chinese district during the Dutch colonial period. In Candra Naya, one can see a blend of Dutch colonial Batavia architecture and southern Chinese styles.

Lohanda (1994) conducts the historical verification of the development of the Chinese executive officer system and the role it played in colonial Indonesia. According to Lohanda, Khouw Kim Au, who received education in the Dutch language, was appointed as a “Majoor,” the highest level a Chinese officer can attain twice, first from 1910 to 1918; and again in 1927 until 1942. At the same time, he was also a leader of the Chinese Indonesians. After Khouw Kim An died in a Japanese concentration camp in 1945, Candra Naya was used by the Sing Ming Hui community group. The name “Candra Naya” has its roots from the Candra Naya school operated by Sing Ming Hui in 1950s.

Candra Naya’s history spans as the site of Chinese Indonesian’s political and social activity for about a century. In 1992, it came under the disposal of the Chinese Indonesian company Grup Modern and became the target for dismantling for rebuilding inside Taman Mini. Between 2000 until 2003, this historical structure became the object of discussions and the issue even went beyond the Chinese Indonesian community. Articles published in the major newspapers such as The Jakarta Post and Kompas obtained attention of the wide range of the readers. However, the approach of both newspapers to the same issue were somewhat different.

In a series of articles published by Kompas, are focusing on the relationship between the PSMTI and the government. For example, one of the articles reports the opposing views to PSMTI, who asked for the dismantling and reconstruction of Candra Naya to Taman Mini from Jakarta governor Sutiyoso and the Jakarta Provincial Government Committee member Andi Tambunan, who possessed a dissenting opinion.

On the other hand, in the Jakarta Post article “Why is Candra Naya a national legacy?” (23 April 2003) alerts about the cultural significance of Candra Naya transcends Chinese Indonesian history. For example, in an article on May 29, 2003 article, it was reported that Candra Naya was the site of the first Indonesian Badminton Association Congress held in 1957. The newspaper also quotes the opinions of intellectuals such as Irma Hatsumi of Indonesia University’s comments as follows: “the building became the headquarters for the Indonesian Student Action Front (KAMI) during the upheaval following the aborted coup in 1965, blamed by most Indonesians on the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), and became the site for raising money for financing the city’s development during the governorship of Ali Sadikin (1966-1977).” These opinion had effect of appealing to the non Chinese Indonesian readers.

The article also quotes a heritage observer David Kwa regarding to its architectural style. Kwa said “It has many non-Chinese touches not found in pure Chinese architecture” and “the window shutters and window bars, marble floor, glass skylight, ironwork ornamentation, which are obviously Indisch-style architecture” and stress that Candra Naya reflects the melting pot Batavian society

Taking these arguments around the dismantling and reconstruction of Candra Naya into consideration, Kusno (2001) points out the significance of Candra Nayaas a symbol Chinese Indonesians society after the riots of May 1998. According to Kusno, Candra Naya is only 100 meters away from the most severely damaged area in by arson in Grodok. It is a building that secures the presence of Chinese Indonesians in the area because of the Chinese characteristic of the building. In addition, because of the Candra Naya is a reminder of the political characters of Chinese Indonesians, which was once snatched away by the Suhrato administration and came back to their hand after the May 1998. Candra Naya therefore represents an symbolic meaning that connects the past and future of Chinese Indonesians in Indonesian society.

With Kusno’s argument, it becomes clear why PSMTI decided to place an replica of Candra Naya in the Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park when the plan for transferring became unsuccessful. It is the importance of Candra Naya as a symbol beyond the architectural design itself that PSMTI tried to adopt.

Museum Exhibitions and Activities

Lastly, I will discuss in a simple manner the contents of the exhibits at the Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park and its proposed activities. The design for the buildings at the park will function as a symbol of Chinese Indonesian ethnicity. The prime purpose of the museum should be to visualization, valuation, and preservation of the culture. As stated earlier, the original plan and the present plan for the park are different. However, since the primary functions of the museum remains the same, my summary will be based on the original proposal.

There will be three buildings that will compose the main parts of the park, namely: the main hall for the museum’s exhibition, the replica of the China town which will include restaurants and souvenir shops and a stage where performances such as lion dances will be held. In the main hall, the following are scheduled to be included: 1) the history of Chinese Indonesians in Indonesia, 2) artworks by Chinese Indonesian artists from different parts of Indonesia, 4) materials relating to heroes, public officials and sports superstars during the country’s hard time, and 5) a library.

Although the details of the exhibits must be waited, the major concern will be how the collective culture, the history, and the future of Chinese Indonesians will be suited in the Indonesian history and society.

Conclusion

In this paper, the details of the plan of the Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park were examined. One can see the paradox involved in this symbolization of ethnicity such as the plan will use the same framework as the Suharto-sponsored Taman Mini, the same administration which restricted the activities of Chinese Indonesians.

At this stage, there is no consolidated point-of-view within the community as to how Chinese Indonesian culture should be symbolized. This is because Chinese Indonesians are still in the process of searching for their ethnic identity. It can be said that after overcoming 35 years of restricted expression, Chinese Indonesians were confronted with the need to create their own ethnicity. They are at the stage of searching for the basis of their identity from China, Indonesia, the Dutch colonial period and the years before the Suharto administration. The case Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park, thus, implies that the creation of ethnicity is born out of an external necessity to form a coherent story with a historical basis.

From now on, what direction will the Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park take? And, aside from the establishment of the museum, how Chinese Indonesian ethnic identity will continue to be reshaped needs to be discussed in further researches. In addition, whether the terms used abundantly in this paper such as “Chineseness,” and “Chinese Indonesianness” can be clearly defined respectably and if so, how to explain them should be clarified in future by conducting comparative researches with other case studies.

Yumi Kitamura

CSEAS, Kyoto University

Kyoto Review of Southeast Asia. Issue 8-9 (March 2007). Culture and Literature

This article was first published in Gensha Vol.1 (2007) and modified and translated by the author.

Bibliography

[Japanese]

青木葉子.2006.「インドネシア華僑・華人研究史」『東南アジア研究』43(4):397-418.

加藤剛.1990.「「エスニシティ」の概念の展開」『東南アジアの社会』矢野暢(編),215-245ページ所収.東京:弘文堂.

———.1993.「飼育されるエスニシティ」『地域研究のフロンティア』矢野暢(編), 153-192ページ.所収.東京:弘文堂, 182-189ページ.

加納啓良.2001.『インドネシア繚乱』文春新書 163.東京:文藝春秋.

クリフォード,ジェイムズ.2002『ルーツ-20世紀後期の旅と翻訳』毛利嘉孝他(訳).東京:月曜社.(Clifford, James. Travel and Transition in the Late Twentieth Century. 1997)

土屋健治.1994.『インドネシア思想の系譜』東京:勁草書房.

[English and Indonesian]

Anderson, Benedict R. O’G. Notes on Contemporary Indonesian Political Communication. Indonesia 16(1973): 38-80.

Badan Koodinasi Masalah Cina-BAKIN. 1979. Pedoman Penyelesainan Masalah Cina di Indonesia. Vol.1. Jakarta: BAKIN.

Kusno, Abidin. Remembering/Forgetting the May Riots: Architecture, Violence, and the Making of “Chinese Culture” in Post-1998 Jakarta. Public Culture 15(1): 149-180.

Lindsey, Tim. 2005. Reconstituting the Ethnic Chinese in Post-Soeharto Indonesia: Law, Racial Discrimination, and Reform. In Chinese Indonesians: Remembering, Distorting, Forgetting, edited by Tim Lindsey and Helen Pausacker, pp. 14-40. Singapore: ISEAS.

Lohanda, Mona. 1994. The Kapitan Cina of Batavia 1836-1942. Jakarta: Penerbit Djambatan.

Pemberton, John. 1994. On the Subject of “Java”. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp.148-196.

Paguyuban Sosial Marga Tionghoa Indonesia. Apa Perbedaan PSMTI-INTI, Buletin PSMTI. No4 (Juli): 5-6.

Suryadinata, Leo. 1997. Political Thinking of the Indonesian Chinese 1900-1995: A Sourcebook. Singapore: Singapore University Press.

———————-. 2004. Indonesian State Policy towards Ethnic Chinese: From Assimilation to Multiculturalism? In Chinese Indonesians: State Policy, Monoculture and Multiculture, edited by Leo Suryadinata, pp. 1-16. Singapore: Times Centre.

Taman Mini “Indonesia Indah”. 1978. What and Who in Beautiful Indonesia I. Jakarta. Taman Mini “Indonesia Indah”.

————————————-. 2004. 20 April 1975-20 April 2004 Taman Mini Indonesia Indah: Pentas Damai Budaya Nusantara.

Tan , Mely G. 2004. Unity in Diversity: Ethnic Chinese and Nation Building in Indonesia. In Ethnic Relations and Nation Building in Southeast Asia, edited by Leo Suryadinata, pp. 20-44. Singapore : ISEAS.

Zon, Fadli. 2004. The Politics of the May 1998 Riots. Jakarta, Solstice Publishing.

Perhimpunan Indonesia Tionghoa. 2006. Undang-Undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 12 Tahun 2006 Tentang Kewarganegaraan Republik Indonesia.

Paguyuban Sosial Marga Tionghoa Indonesia. 2004. Proposal Pembangunan Museum Budaya Tionghoa Indonesia Taman Mini Indonesia Indah Jakarta. Jakarta: Paguyuban Sosial Marga Tionghoa Indonesia.

——————————————————–. 2005. Panitia Pembangunan Taman Budaya Tionghoa Indonesia Taman Mini Indonesia Indah. Laporan Relaksaan Pembangunan Taman Budaya Tionghoa Indonesia Taman Mini Indonesia Indah.

Taman Mini “Indonesia Indah”, Bagian Humas. 2006. Data Jumlah Pengunjung Taman Mini “Indonesia Indah” Tahun 1975 S/D 2005.

———————————————————–. [2006] Daftar Proyek-Proyek: List of Projects Taman Mini “Indonesia Indah”.

[Newspaper (Internet edition)]

The Jakarta Post URL:http://www.theThe Jakarta Post.com

Candra Naya Escapes Wrecker’s Ball. January 29, 2000.

Candra Naya: A Heritage Alredy Forgotten? April 23, 2003.

Candra Naya Relocation Rejected. April 25, 2003.

Sutiyoso Advised to Protect Candra Naya Building. May 13, 2003.

Candra Naya Relocation is Legal Violation. May 24, 2003.

Candra Naya, Test of Commitment to Preservation. May 29, 2003.

Council Supports Candra Naya. June 02, 2003.

Chinese in Taman Mini. April 19,2007.

Kompas URL:http://www.kompas.com

Dinas Museum: Candra Naya Tak Boleh Dibongkar. Mei 12, 2003.

Soal Candra Naya, Pemprov DKI Berpegang pada Peraturan. Mei 22, 2003.

DPRD: Gedung Candra Naya Jangan Dibongkar. Mei 29, 2003.

Marco Kusumawijaya. Pemeliharaan Candra Naya Tak Perlu Ditawartawarkan. Juni 19, 2003.

Proyek Taman Mini Budaya Tionghoa Kesulitan Dana. Juli 26, 2006.

Notes:

- Clifford borrowed the concept “contact zones” from Mary Louise Pratt’s “Eyes of Empire: Travel and Transculturation” (Pratt 1992: 6-7) (Clifford 1997: 192). ↩

- The word “Cina” is considered a derogatory term among Chinese Indonesians. However, the term is the easiest word to use to denote Chinese Indonesians among the general population. There is an on-going complaint to change the term to “Tionghoa” in public documents. ↩

- Refer to Kato (1990) for the terms. ↩

- he total number of the victims varies depending on the source. Fore example Republika quotes the Social Institute of Jakarta as over 1000 and the National Commisition of Human Rights as 1188 in June 5, 1998 issue. Suara Karya reports as 1217 in the issue of June 10, 1998. In this paper, number is quoted from Kano (2001:33) ↩

- In 1991, President Habibie instructed all government bodies to abolish discrimination against Chinese Indonesians . In 2000, President Wahid repealed Presidential Order No. 14 of 1967 which prohibited the practice of Chinese culture, tradition and religious activities and the public display of Chinese symbols. Moreover, in 2002, President Megawati, through Presidential Decision No. 19, made the celebration of the Chinese New Year a national holiday starting from the year 2003. ↩

- The obligatory possession of the certificate of nationality by Chinese Indonesians (Surat Bukti Kewarganegaraan Republik Indonesia : SBKRI)was abolished by this law. ↩

- Refers to the President Instruction NO.37 of 1968 on Main Government Policies on People of Chinese Descent (Instruksi Presidium Kabinet No.37/U/IN/6/1967. Tentang Kebijaksanaan Pokok Penyelesaian Masalah Cina). ↩

- Although Tan (2004: 33-39) treated both groups separately (PSMTI as a mutual aid group; INTI as a pressure group) in her paper, both were considered as the same kind of group under the same umbrella organization. ↩

- Information courtesy of PSMTI. ↩

- From September 31, 1965 until October 1, lieutenant-colonel Untung was involved in the abduction and murder of Chief of Staff Yani and 6 generals. After this incidence, Suharto made a sweeping operation against communist parties in Indonesia. In March 1966, through “the order of March13” taking substantial powers from Sukarno, Suharto became acting president by 1967 and eventually assumed the presidency in March 1968. ↩

- According to Anderson (1973) Tien Suharto visited Bangkok in March 1970 saw the similar miniature park Timland and pointed out the possibility of a Presidential first ladies network acting in the background. According to Pemberton (1994), on 20 April 1975, the opening of Taman Mini, the Philippine President’s first lady, Imelda Marcos present for the event. In June 1970, a similar miniature park, Nayong Pilipino, was opened. If we look at it, the possibility of a first ladies’ network in South-east Asia that pushed for the cultural projects was not far-fetched. ↩

- n 2002, East Timor became an independent nation. At present, only the signboard that says “museum” was replaced and the East Timor pavilion is left at the site. However, since maintenance work has not been done, when I visited the site on September 2006, it was in a state of disrepair. ↩

- On 13 and 15 March 2006, according to the PSMTI publicist. ↩

- Based on a series of articles from Kompas and The Jakarta Post. ↩

- Ali Sadikin, was the Governor of Jakarta from 1966 until 1977, not only contributed to the building of Taman Mini but also to the urbanization of modern Jakarta. ↩

- 7 March 2006, from the Taman Mini publicist. ↩

- 18 July 2006, from Mr. Z, a professor at Tarmanegara University and deeply related with the preservation efforts at Candra Naya ↩

- After the 2006, the articles of the Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park was reported Kompas (June 26, 2006) or The Jakarta Post (April 19, 2007). Financial difficulties are also reported in these articles. ↩

- Pointed out by a few Chinese Indonesian intellectuals in Jakarta during my interviews. ↩

- August 2003, from the Chinese Indonesian Cultural Park office in Taman Mini. ↩

- For example, the residential areas in Jakarta’s suburbs, the Chinatown shopping arcade atmosphere in Kota Wisata uses the Forbidden City. Forbidden City seems to be accepted as a representative of Chinese architecture. ↩